Intersectionality: A requisite perspective on neuroscience research

- BrainSightAI Team

- Feb 1, 2022

- 7 min read

Neuroscience and its study often leads to the epiphany that who we are and what we do centers around our synaptic connections. While neural structures significantly determine our experience, who we are is also rooted in the tangible feature of identity. Similar to the brain, one's identity is made up of building blocks, like gender, race, socioeconomic status, education, and so on. The interconnected nature of such social and political identities of people, that give rise to certain privileges and disadvantages, can be understood by the framework of intersectionality (Crenshaw, 1991). Neuroscience and psychology have shown that experience and behaviour can most certainly impact neural structures, and vice versa. In a similar fashion, the interwoven facets of identity lead to unique experiences for different people. Therefore, the themes of intersectionality, psychology and neuroscience together are a pressing scope of study.

The interplay of different characteristics of identity on the domain of health.

This blog focuses on Annie Duchesne and Anelis Kaiser Trujillo’s (2021) work which reviews the benefits and risks of exploring intersectionality-informed neuroscience. The focus is on neurofeminist practices, which is a contemporary take on brain research. Neurofeminism critically questioned and examined gendered impacts of neuroscience research in order to develop research approaches that are gender-appropriate; that address the role of gender/sex in brain structure and function (Eliot, 2011). Duchesne & Trujillo prescribe an analytical perspective for re-evaluating methodological constraints and knowledge productions within the neurosciences. Based on this, further segments of the blog will take a look at various aspects of neuroscience research through an intersectional lens.

Such efforts to inculcate a new wave of research approaches which value diversity in the neurosciences is commendable, and also forms the crux of the outlook we, at BrainSightAI, want to adopt in this blog and in our own methodology of study.

An intersectional research question

Research that employs intersectionality tends to conceptualize social group memberships such that they guide the research question, with the aim to develop concrete actions for social change (Duchesne & Trujillo, 2021). The social structures taken into account are complex, and generally influence various aspects related to the phenomenon under study.

One such study by English et al. (2020) investigated socio-structural factors related to psychological health and health-behavior outcomes within HIV-positive, Black sexual minority men. A history of incarceration by law enforcement showed direct and indirect relationships to worse psychological health outcomes for this particular population, including risky sexual behaviours and decreased motivation to seek prophylactic treatment. The rationale behind the research question was that while there is awareness of the discrimination faced by sexual minorities of colour, there is little research which examines how these stressors may drive HIV and psychological health inequities among these men. By questioning and exposing the socio-structural factors associated with health inequality within certain group memberships, this type of intersectionality research provides an understanding of health that is directly linked to power dynamics, and offers an approach to studying health and wellness that has the capacity to promote social change (Duchesne & Trujillo, 2021).

Neuroscientific research should aim to study the neural ramifications of health inequalities as a consequence of experiences related to social group memberships. To advance intersectionality within neuroscience, the process of composing the area of study and the related research question must follow a set of ideal approaches. Firstly, explicitly approaching dimensions of identity as interdependently constituted of and with other social group memberships is a critical area for advancement. Second, increased focus should be placed on conducting research with populations of diverse and marginalized groups of people that are often rendered invisible. The goal is for intersectional researchers to formulate how specific socio-structural power dynamics may contribute to or fully explain previously observed identity-related brain health inequalities (Buchanan & Wiklund, 2021). Finally, methodologies and analytical approaches that allow for the socio-historical contextualization of oppression and privilege must be selected, as will be discussed further (Duchesne & Trujillo, 2021).

Methodological Considerations

The second theme of psychological research informed by intersectionality relies on quantitative methodologies to provide an understanding of how information-processing related to different social categories may underlie processes of social discrimination.

Many seminal studies in psychology on processing of racial recognition and bias are in existence. However, such studies focused heavily on the perception of certain racialized phenomena, mostly by homogeneous and usually privileged participants, and this “general” investigation runs the risk of partially binding results to support existing unequal power dynamics. (Duchesne & Trujillo, 2021).

Now, with the integration of intersectionality in psychological research, there has been a diversification of identity stimuli as well as participant samples. It has been recognised that what is considered "masculine" or "attractive" is rooted in cultural and socio-structural groups and dynamics. Alternatively, the focus now rests on using an intersectional lens to understand the experience, rather than the perception, of identity as a stimulus. Chaney et al (2020) conducted a study investigating how participants’ own sex/gender and race relate to perceived safety and threat cues in Black, Latina and white women. It demonstrated the anticipation of discrimination (a threat) or safety from an identity threat stimulus or safety cue respectively, which was designed to target a part of their stigmatized identity (Chaney et al, 2020). At the psychological level, intersecting marginalized social identities confer disadvantage and advantage depending on the social situation, thus showing the ramifications of power imbalance in social inequality.

In neuroscience research, many studies investigate the neural correlates of social categories, but only using narrow constructs of identity. A study by Stolier and Freeman (2016) suggests that social categories of identity and emotional expression are inherently intertwined, as shown by similarities in neural patterns. Their behavioral and fMRI experiments employing representational similarity analysis demonstrate that both the subjective perception and neural representation of social categories is contingent on participants’ social knowledge of identity-related stereotypes. For instance, in emotional categorization, Black faces were disproportionately categorized as angry, while female faces were disproportionately categorized as happy (Duchesne & Trujillo, 2021). However, future studies must counterbalance the weaknesses of such studies, by pondering the question of whether the subjective stereotypes are fixed at the brain level, or if they can be changed. Furthermore, developing studies that not only manipulate social group stereotypes, as done by Stolier and Freeman, but also manipulate the social power dynamics, could provide new insights into the brain processing of sex/gender (Duchesne & Trujillo, 2021).

Interpretation of findings and Epistemology

The third approach employs intersectionality to interrogate how psychological knowledge is produced and understood, and in doing so, challenges psychological epistemology (Duchesne & Trujillo, 2021). In research that employs intersectionality, critical analysis of identity is important to understand the outcomes of identity on the studied variables. Ultimately, the emphasis is on dismantling inequitable conditions, and bringing about social justice with the help of analysis and interpretation that is free of bias.

Historically, results in psychology research have been rooted in scientific evidence. On the other hand, the intersectional perspective to research is an approach to limit generalizability and the shortcomings of prior study and experimentation. Hence, intersectional psychological research faces a barrier here - one of epistemology. "Generalizable'' explanations of psychological knowledge and phenomena are distorted intersectionally. This is because the researcher's social position comes into play, informing every step of study. An intersectional perspective necessitates that psychological knowledge, theory, and research must be oriented toward social justice actions and goals, making social activism a central consequence of advancing psychological knowledge (Settles et al., 2020). Conceptual and methodological shifts are currently being observed in the involvement of the participant as co-creator of the research.

Neuroscience researchers propose that the practice of intersectional neuroscience should favour analytical approaches to understanding the brain that “accommodate neural diversity”. To preserve the brain’s individuality but still allow for comparison between subjects, Weng et al. (2020) recommend using multi-voxel pattern analysis (MVPA), a multivariate method that uses machine learning to derive brain activity patterns predictive of mental states, without requiring normalization of brain data. At the same time, intersectional neuroscience should be concerned with conducting research that includes hidden, underrepresented, and marginalized populations and involve a process of “partnering” with participants rather than generating information “about” them. Such an approach minimizes the “generalization” that arises from ignoring intersectionality.

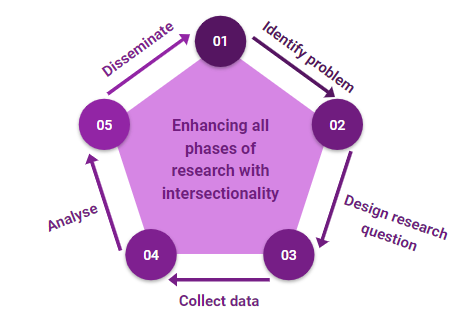

An approach to enhance research practices with intersectionality.

Intersectionality has the capacity to broaden the scope of neuroscience research, just the way it has established this feat in psychology. The aim is to revolutionize the field by having a neuroscience of inclusivity and similarities, rather than a neuroscience of differences.

________________________________________________________________________

References

1. Buchanan, N. T., and Wiklund, L. O. (2021). Intersectionality research in psychological science: resisting the tendency to disconnect, dilute, and depoliticize. Res. Child Adolesc. Psychopathol. 49, 25–31. doi: 10.1007/s10802-020-00748-y

2. Chaney, K. E., Sanchez, D. T., and Remedios, J. D. (2020). Dual cues: women of color anticipate both gender and racial bias in the face of a single identity cue. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 2020, 1–19. doi: 10.1177/1368430220942844

3. Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color. Stanford Law Rev. 43, 1241–1299. doi: 10.2307/1229039

4. Duchesne, A. & Trujillo, A. K. (2021). Reflections on Neurofeminism and Intersectionality Using Insights From Psychology. Frontiers in human neuroscience, 15, 475. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2021.684412

5. Eliot, L. (2011). The trouble with sex differences. Neuron. 72, 895–898. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.12.001

6. English, D., Carter, J. A., Bowleg, L., Malebranche, D. J., Talan, A. J., and Rendina, H. J. (2020). Intersectional social control: the roles of incarceration and police discrimination in psychological and hiv-related outcomes for black sexual minority men. Soc. Sci. Med. 258:113121. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113121

7. Fine, C. (2012). Explaining, or sustaining, the status quo? The potentially selffulfilling effects of ‘hardwired’ accounts of sex differences. Neuroethics 5, 285–294. doi: 10.1007/s12152-011-9118-4

8. Pitts-Taylor, V. (2019). Neurobiologically poor? Brain phenotypes, inequality, and biosocial determinism. Sci. Technol. Hum. Values 44, 660–685. doi: 10.1177/0162243919841695

9. Schmitz, S., & Höppner, G. (2014). Neurofeminism and feminist neurosciences: a critical review of contemporary brain research. Frontiers in human neuroscience, 8, 546. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2014.00546

10. Settles, I. H., Warner, L. R., Buchanan, N. T., and Jones, M. K. (2020). Understanding psychology’s resistance to intersectionality theory using a framework of epistemic exclusion and invisibility. J. Soc. Issues 76, 796–813. doi: 10.1111/josi.12403

11. Stolier, R. M., and Freeman, J. B. (2016). Neural pattern similarity reveals the inherent intersection of social categories. Nat. Neurosci. 19, 795–797. doi: 10.1038/nn.4296

12. van Anders, S. M., and Gray, P. B. (2015). Social neuroendocrine approaches to relationships,” in Emerging Trends in the Social and Behavioral Sciences: An Interdisciplinary, Searchable, and Linkable Resource, eds R. A. Scott and M. C. Buchmann (Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons), 1–15. doi: 10.1002/9781118900772.etrds0309

13. van Mens-Verhulst, J. & Radtke, L. (2008). Intersectionality and Mental Health: A Case Study.

14. Weng, H. Y., Ikeda, M. P., Lewis-Peacock, J. A., Chao, M. T., Fullwiley, D., Goldman, V., et al. (2020). Toward a compassionate intersectional neuroscience: increasing diversity and equity in contemplative neuroscience. Front. Psychol. 11:573134. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.573134

Comments